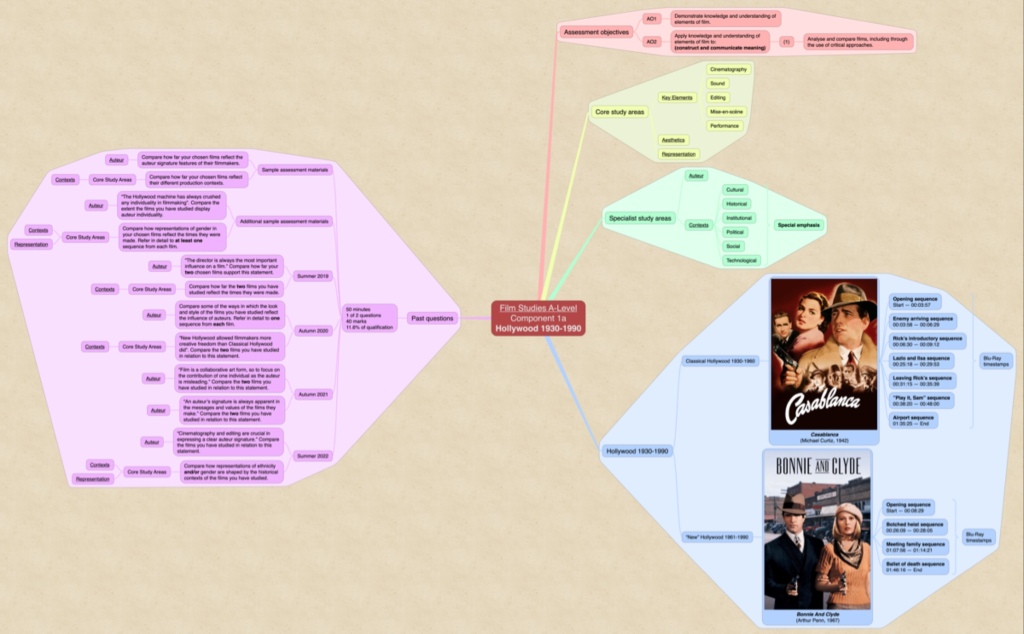

“Compare how far your chosen films reflect their different production contexts.”

Planning:

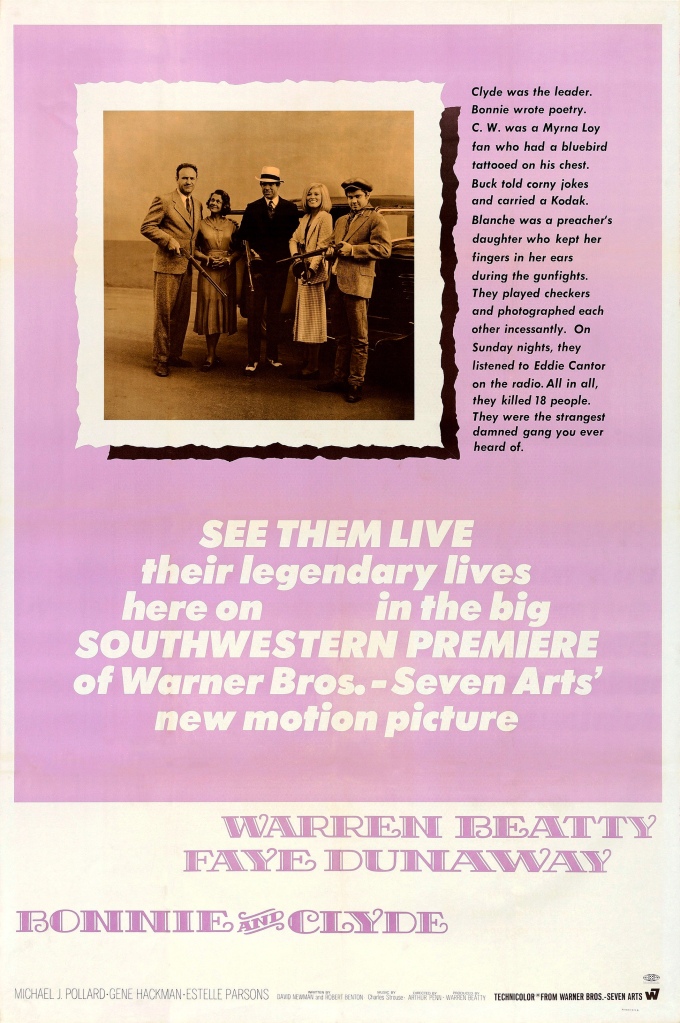

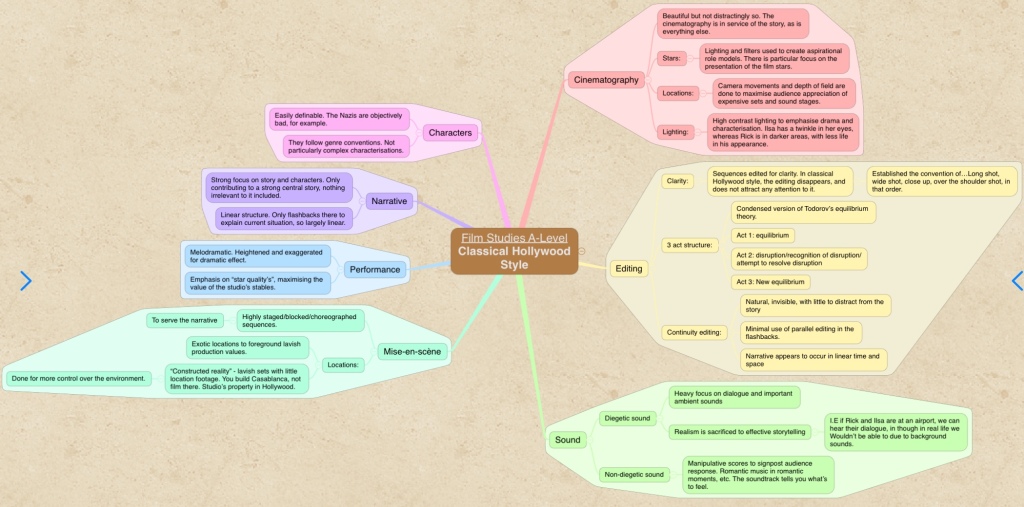

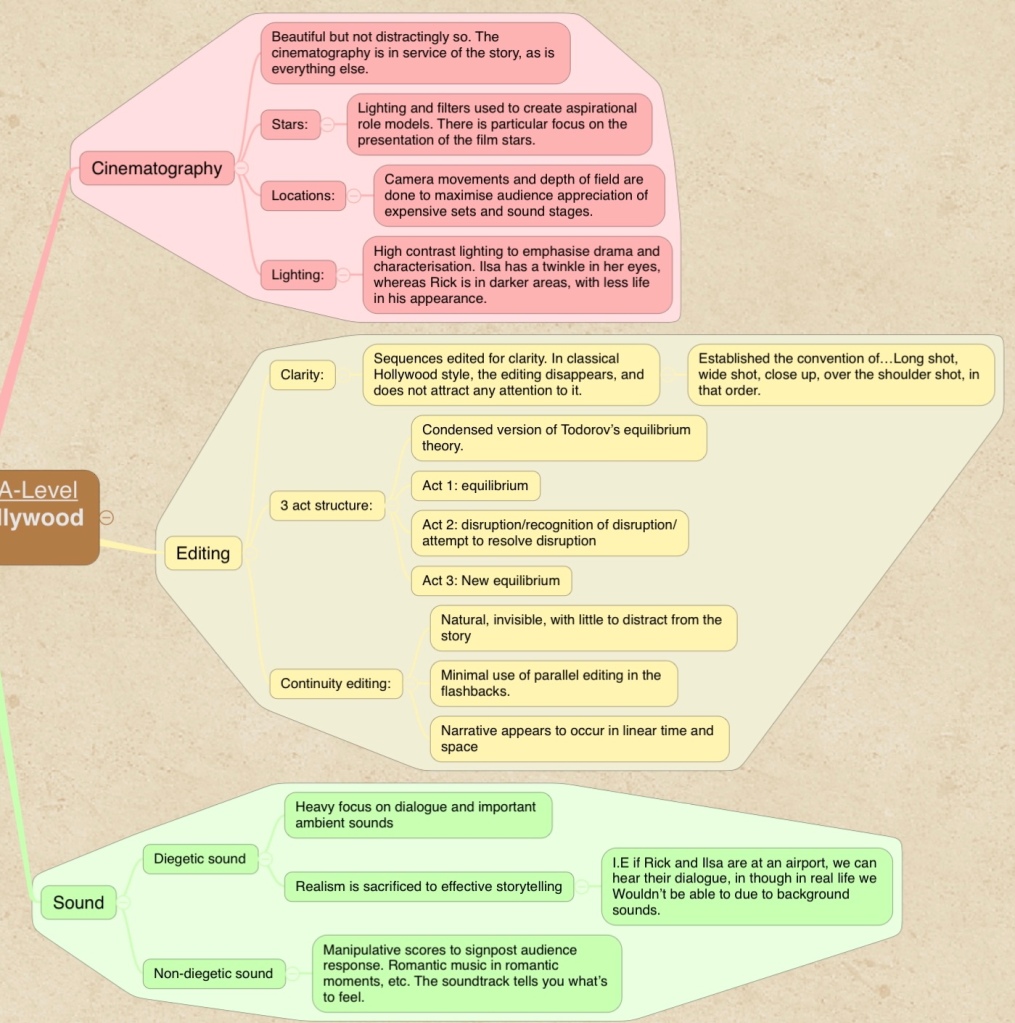

Introduction – Overview of how Casablanca was influenced by the context of the ‘Golden Age of Hollywood’ and the studio system it was produced in, and the same for Bonnie and Clyde and the ‘New Hollywood’ alongside the French New Wave and the 1960s as a whole.

Talk about ‘Ricks introductory Sequence”, particularly focusing on the cinematography and sound design, editing and representation. Talk about how this is a result of the Studio System and Classical Style and WW2 contexts. For Bonnie and Clyde, talk about how the opening sequence differs from the Classical Hollywood Style in its jarring close ups with lack of establishing shots, but compare in the way that the lead stars are presented. Make sure to compare each element of each film, i.e cinematography or performance, to examples of the same element from the chosen sequence of the other film.

Comment on how the ‘Leaving Rick’s’ sequence is shot, how the characters/actors are represented, and how the editing and sound design are incorporated to create a seamless feel to it. Then, compare this to the ‘Meeting Family’ sequence, focusing on this scenes blatant differences to Classical Hollywood and similarities to the French New Wave.

Conclusion – Focus in on how the objectives of the directors changed between the times that both films were made. Consider that in the 1940s, it was about sleekness and seamlessness, keeping attention on the story and the actors, whereas in the 1960s filmmakers inspired by the French New Wave wanted to defy conventions and produce casual, low budget films.

Version 1:

Casablanca and Bonnie and Clyde reflect the social, cultural and institutional contexts they were made in to a large extent. The former was made in a time period where focus was placed on the story, helped to be communicated through seamless editing and smooth, unnoticeable cinematography, the latter inspired by foreign film movements that placed emphasis on going against convention and utilising casual, cheap film production.

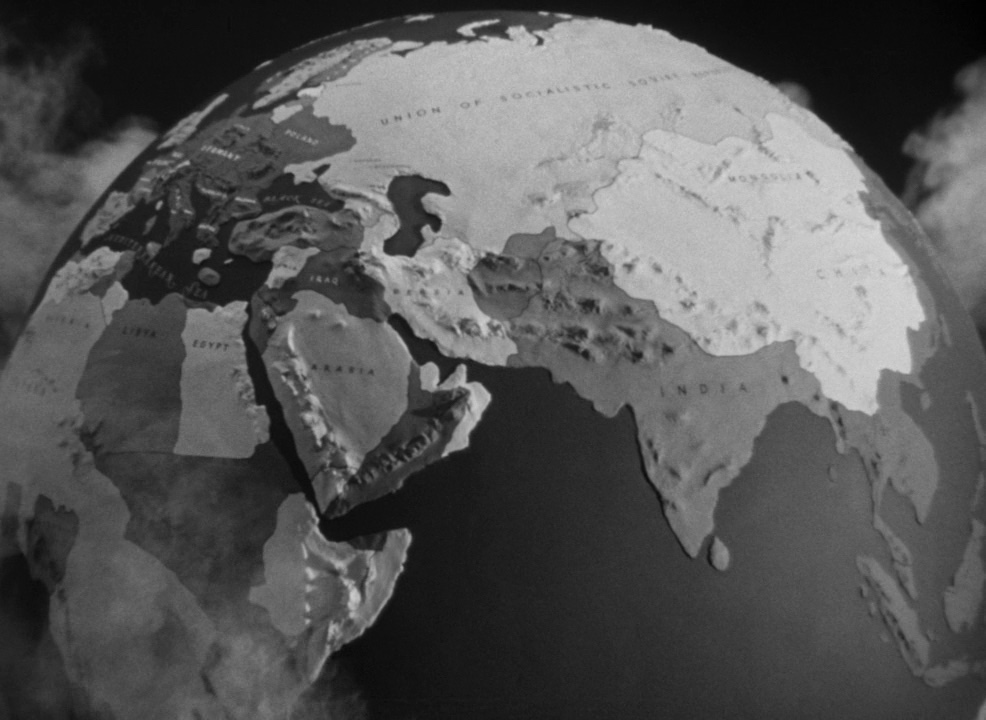

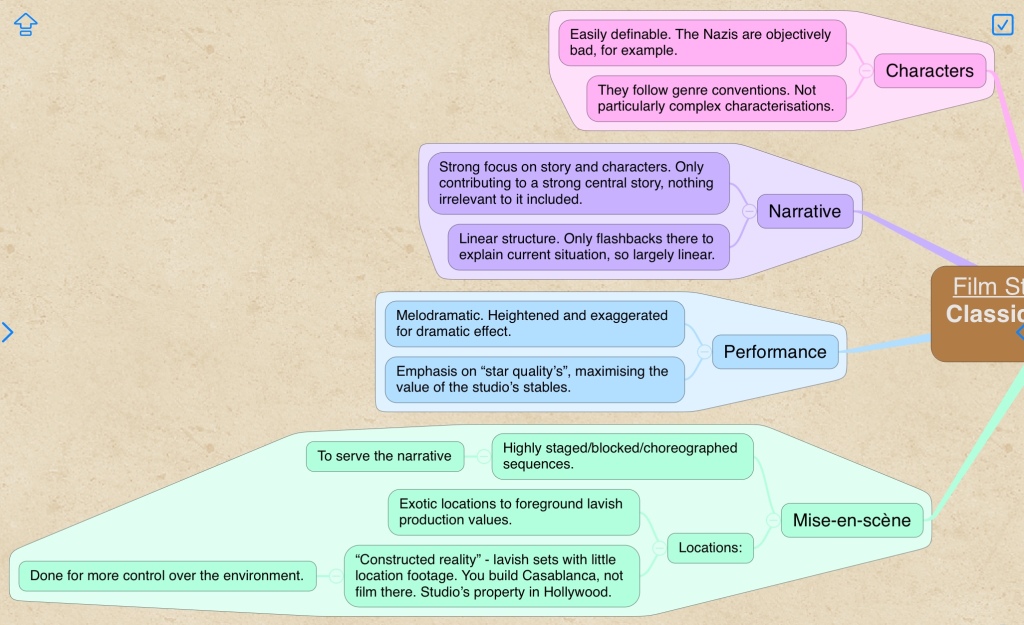

Casablanca was made during the ‘Golden Age of Hollywood’ where the Classical Hollywood Style, a method of filmmaking that focused on remaining unnoticed to the audience and entirely serving to communicate the story, was dominant. This can be seen in the camerawork of ‘Rick’s introductory sequence’, which begins with a typical long shot to establish the location for the audience, then cutting to a close up of the cafe’s sign to bring their attention to the specific location of the scene. The camera then smoothly tilts down and follows behind a group of customers entering the cafe, a moment in which the gliding movement done with only two cuts so far is used to immerse the audience in the environment, further done by the doorman holding the door for the camera and a waiter acknowledging it. On the contrary, Bonnie and Clyde was made after the collapse of the Hollywood studio system, after which theatres, no longer directly owned by the production companies, had the freedom to show new, foreign films. This led to a rise in filmmakers inspired by the French New Wave, such as Arthur Penn and Warren Beatty, who incorporated the style of filmmaking from the New Wave, which emphasised a casual approach to making the film, often being self-aware and provocative. This can be seen in the opening sequence of the film, which immediately begins with an extreme close up of Bonnie’s lips, without the preamble of an establishing shot, jarring the audience. This opening shot also immediately sexualises her, alongside the later use of sexual imagery done through the coke bottles and Clyde’s gun, which is felt suggestively by Bonnie. This reflects the increasing acceptance of sexual imagery in America in the 1960s, which Bonnie and Clyde includes often, therefore bypassing the Hays Code, which Casablanca adhered to by avoiding violence or sexual imagery. The rest of the opening scene in Bonnie’s bedroom plays through tight close ups of her face, obstructing the room from view and emulating her feeling of being trapped and constrained, deliberately avoiding the classical convention of establishing where the scene takes place. Therefore, both films reflect their production contexts, through their approach to conveying information to the audience, to a large extent.

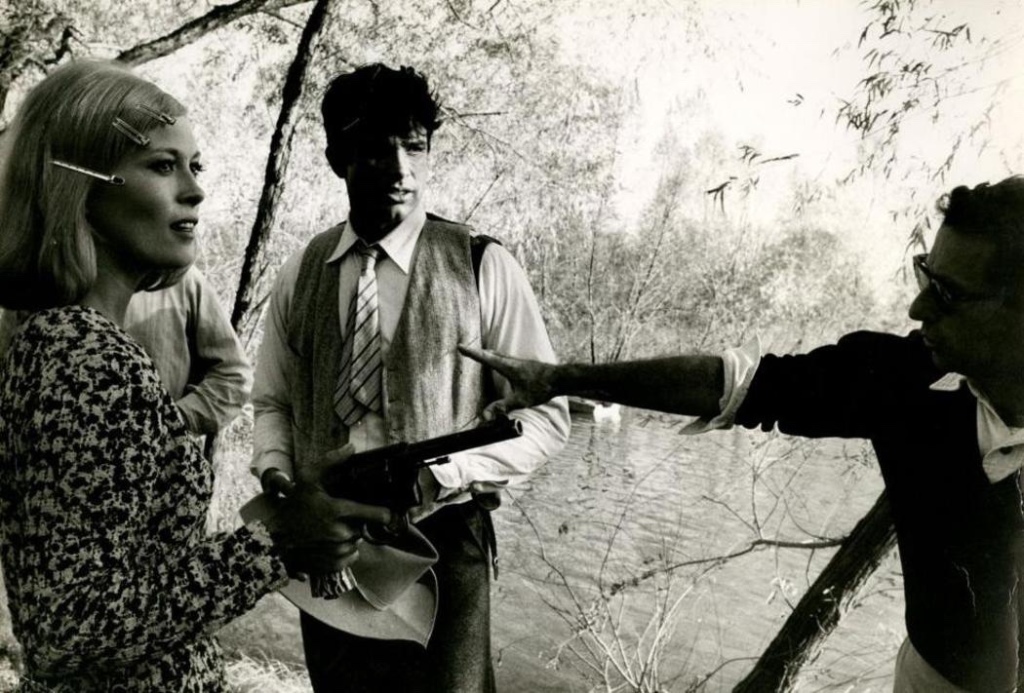

The sound design in Casablanca in ‘Rick’s introductory’ sequence is smooth and unnoticeable to the audience, the composed diegetic sounds of Sam playing and people talking growing in the mix as the camera nears him and those crowded around him. This, alongside the constant background ambience of conversations in the cafe and the way these subtly subside in the sound mix when the audiences attention is being focused on dialogue, serve to immerse the audience in the film and keep their attention on the story and the setting it takes place in. The films also cuts, in Classical Hollywood Style, as little as possible, utilising smooth, subtle camera movements and carefully choreographed actors to show what is of importance in frame, such as two people talking, and only cuts to bring us deeper into the cafe, keeping the audiences attention away from the technical aspects of how the film is made. Bonnie and Clyde, in it’s opening sequence, has an undertone of faultiness in how it was made, as when Bonnie first speaks, the diegetic dialogue is loud and jarring. In contrast, when they speak outside, the dialogue sounds distant and muffled, hard to make out. This prevents the audience from becoming completely immersed in the dialogue of the story. The films also goes against Classical Hollywood convention of showing the action by avoiding showing Clyde commit the robbery, remaining outside as he goes in with a gun. This purposefully denies the audience the pleasure of seeing the action, inspired by the French New Wave style of focusing on the characters and their personal journey rather than just the crimes they commit, although the consequences of their actions and the violence they commit do play a key role in the film. Therefore, both films reflect their production contexts to a large extent through their approaches to cinematography and sound design.

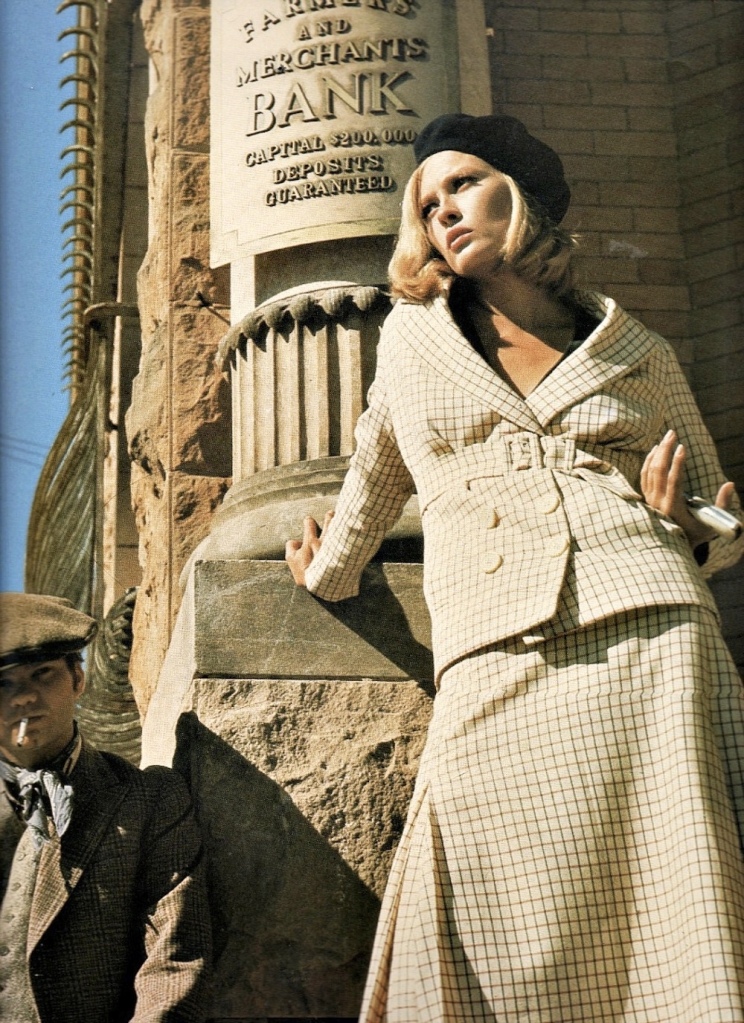

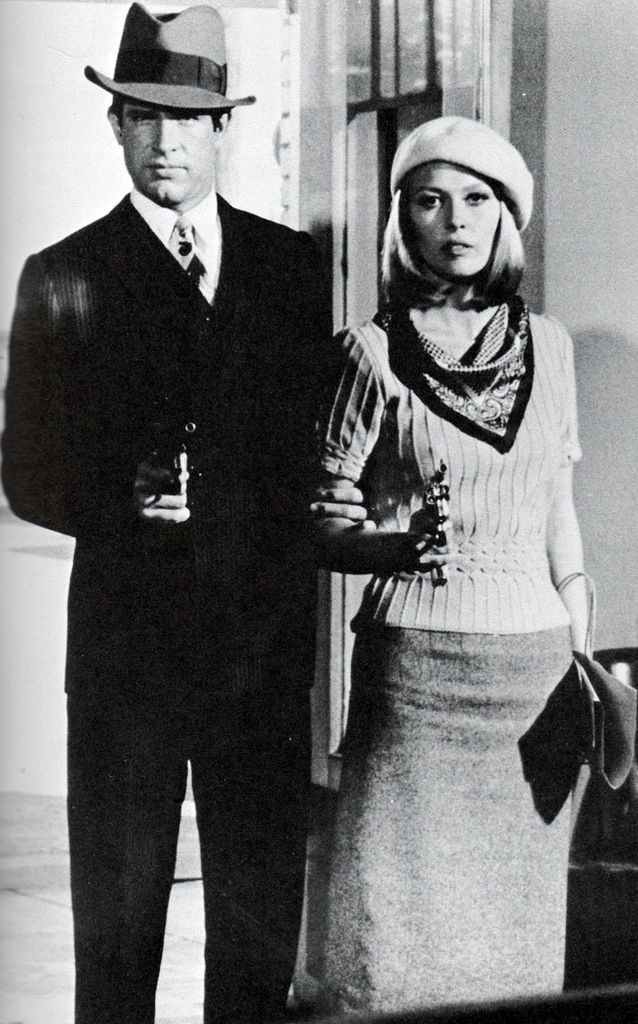

The influence that the Hollywood Star System had on Casablanca can be seen in the ‘Leaving Rick’s’ sequence. Here, the cinematographer ensures that Ingrid Bergman, a popular star that Warner Bros. Had a contract with, looks as glamorous and beautiful as possible. She is presented is close ups, such as when she talks to Rick, by herself, to keep the audiences attention on her, in which the side of her face she preferred is shown, catch lights in her eye give them a lively sparkle, and the careful composition of the light on her face presents her as elegant, fragile and flawless, if unrealistic, in her appearance. Bonnie and Clyde strives for a more naturalistic beauty in the opening sequence, where Faye Dunaway in shown simply with makeup to present her as a more relatable and real, though still a renowned film star, protagonist for the audience to follow, as in the French New Wave style of real, typically working-class protagonists fighting against the establishment. In Casablanca, Humphrey Bogart is introduced to the scene in a low-angle shot, presenting him as a physically larger character, framed by an overhead arch, centre frame, to keep the audiences attention on him. Bonnie and Clyde simply shows Clyde from above, without a close up or carefully composed frame to signify his importance. He is also portrayed as a flawed protagonist in the film, evidenced by his limp from losing a toe in prison as he approaches the store to rob it. On the contrast, Rick seems constantly in control of the situation, carrying an air of causal calm about him at all times. This shows that both films reflect the contexts in which they were made to large extents, through their approach to representing the actors and focusing the audiences attention on them.

In Casablanca’s Leaving Rick’s sequence, the camera carefully rises and falls when the actors do, such as when Lazlo sits and it pedestals down to track him. Actors are carefully choreographed to keep our attention on certain significant things in frame, such as when Renault turns and calls for a waiter, revealing one, distant and unimportant in the background, but still there for the audience to see who he is speaking to. This smooth and seamless camerawork allows for the scene to continue on for some time before cutting to get closer to the characters, keeping the audiences attention on their conversation rather than the editing. Bonnie and Clyde, on the other hand, uses distracting editing in its ‘meeting family sequence’, such as the sudden and inconsistent slow motion shots when the kids roll down a hill, then having reached the bottom by the start of the next shot, and the non-temporal cut from one shot of Bonnie throwing sand to her hugging her mother in the next. These unusual and non traditional approaches to editing are disorienting for the audience, also done through the strange, hazy filter the scene is shot through, giving it a dream-like, surreal quality. This scene also features many sudden moments of eerie silence, such as when it cuts to Moss stood on the hill, which makes the scene feel imperfect in its production. Another way the films reflect their production contexts is in the approach to shooting on sets or location. Casablanca was made during the Hollywood Studio System, where the big eight film studios owned sets which they would display in films through shooting on superficial locations created through lavish set design. This is evident in Casablanca, as Rick’s expansive, lively, exotic and bustling cafe is designed meticulously in such a way to allow the camera to move through it, conveying the story and the expensive, detailed set. Bonnie and Clyde, in the style of the French New Wave style of filmmaking, favours a naturalistic approach, and shoots on location, evident in how the background of the picnic area is a decaying, abandoned industrial site, reflecting the backdrop of poverty during the Depression Era, but shot in rural Mid-West America, where some areas were still recovering financially from that period. Therefore, through their approach to editing and shooting on locations, these films reflect their production contexts to a large extent.

Both films reflect the production contexts that they were made in to large extents. In Casablanca, it is clear through the smooth cinematography and sound design, lack of editing, high emphasis on the stars, and shooting on superficial, constructed reality sets, that it was largely a product of the Classical Hollywood Era, which sought to keep focus on the story and the stars. Bonnie and Clyde was heavily influenced by the French New Wave and the rising acceptance of sexuality in the 1960s, which is seen through the films flawed, distracting editing, jarring and disorienting cinematography, unfitting sound design and naturalistic approach to presenting its stars and shooting on real locations, where they adapted to the environment to film.

You must be logged in to post a comment.