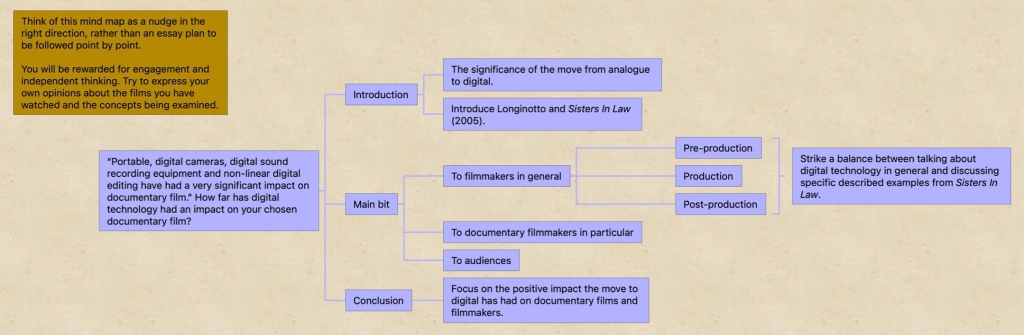

“Portable, digital cameras, digital sound recording equipment and non-linear digital editing have had a very significant impact on documentary film.” How far has digital technology had an impact on your chosen documentary film?

Plan:

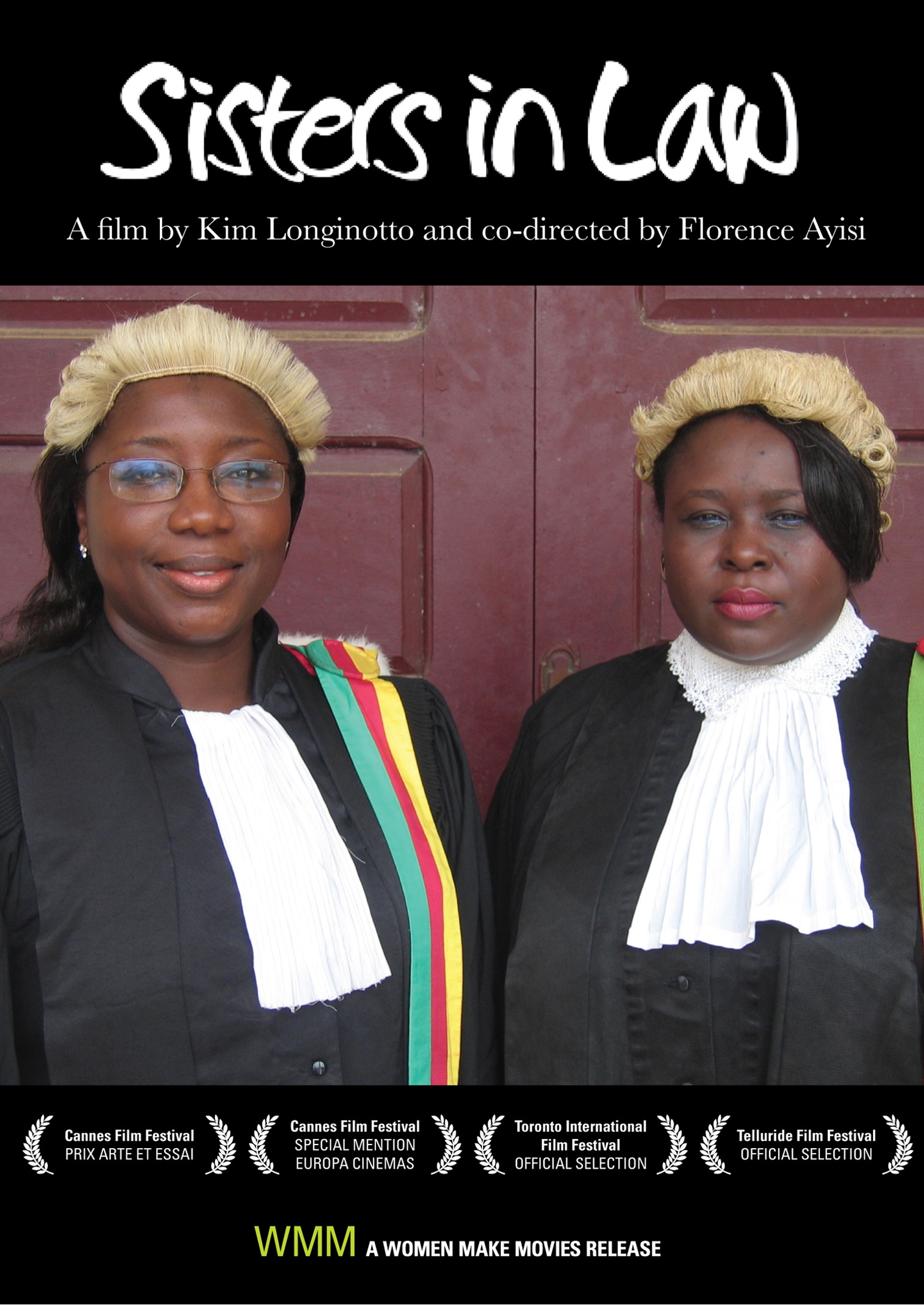

Intro – briefly evaluate the significance of digital technology for documentary films and list the main reasons why – portability of digital cameras, digital audio and editing were positive for it. Then introduce Sisters In Law.

Para. 1 – Discuss the opening sequence and pick apart the aspects of digital technology in the question.

Para. 2 – Discuss the aspects of digital technology in the opening sequence.

Para. 3 – Manka sequence. Remember to keep in mind editing, audio and digital cameras are seen in the film and were used in its production tot he filmmaker’s’ advantage.

Para. 4 – Manka Sequence.

Conclusion – Link back to question, evaluate overall impact on documentary film through positive effects on production.

Version 1:

Digital technology has impacted Sisters In Law (Kim Longinotto, 2005)to a large extent. Digital audio equipment, digital camera technology and editing have made it easier for Kim Longinotto to gain high quality footage and documentation of their subject without making any sacrifices during the production process.

In the opening sequence of Sisters In Law, the camera shows the view from inside a moving car, introducing us to the village the film will be set in. The camera used here is steady and captures the view from outside the window clearly, in good quality footage. This is the first time that the portability of digital cameras can be seen in the film, as the camera being used here fits into the back of this small car. The first show we see of the office is a man parking his bike up. This shot, alongside those inside the office, were included in the final film after the editing process because Longinotto was able to film for long periods of time, capturing lots of footage of this village so that she could choose which clips to keep in the film. This is because the digital cameras hold near limitless storage, so that the filmmaker can film for as long as they want, as seen in the opening shot to this sequence, and decide what to include in the film in post-production. The lightweight nature and portability of digital cameras allows for Longinotto to film in these cramped office conditions without getting own the employees’ way, since the small camera can just be moved when needed. These digital cameras can also film in natural and low light conditions, as seen inside the office, without the need of obtrusive artificial lighting, and the end product of the footage is still high quality.

There is also no need for a boom-stick to pick up audio here, since there is a non-directional camera built into the camera. This means that there is no large audio device taking up space in the room, making sure that no employees are distracted by the camera crew since their small and portable equipment keeps them unobtrusive. This non-directional microphone also does not need to be aiming at a specific subject to capture audio from them, and just one digital camera can capture good quality audio from around the entire room without using bulky, heavy and obstructive equipment. Digital cameras are also cheaper than film cameras, so two were bought for Sisters In Law, and we can see this from how the film cuts between them both. This allows for more footage to be captured, as seen here from where the camera cuts from a shot of a woman setting up her desk in the office and answering a phone to a man in the lawyer’s office the next room over. But despite there being more cameras here, they still take up little more space as they are so small and portable. The audio from the office has also been edited to play over the footage of man in the lawyers office, so that we can hear the conversation playing out in one place but also be immersed in the environment from the clip of the office, making us, the audience, feel like we are really there. The digital camera can zoom in on objects of significance, such as the wife who is giving her story, to focus the audience’s attention on them without physically moving the camera and distracting the participants. The compact nature of the cameras also leads to people sometimes forgetting that they are there and giving a genuine reaction to things, such as when the lawyer shouts “That’s what you men do” at the husband, which allows for more authentic aspects of these people and life in the village to be captured.

Digital camera technology has also had a significant impact on the production of the Manka sequence. The camera is small and compact, remaining unobtrusive in the lawyer’s small office as it takes up significantly less space than a film camera would. This prevents it from being distracting at any point for the participants in the documentary, such as the small child Manka, who does not look at it more than once throughout the whole scene. It also allows for Longinotto to point the camera at whatever is relevant in a specific moment, such as the lawyer, who she pans right to show as she gives a reaction to the aunt’s actions. The lawyer’s reaction, a brief moment of anger, was also made possible by the size and portability of the digital cameras, as the lawyer likely forgot that they were there and so gave a completely honest reaction in the heat of the moment. These digital cameras can also zoom, so Longinotto can bring the audiences specific attention to something, such as the aunt’s reaction to what she has done when it zooms in on her face as the lawyer questions her, or in this case the scars on Manka’s back, making the audience feel sympathetic for her and avoiding having to physically move closer to capture it on camera, interrupting the proceedings. The camera also automatically refocuses when it pans right to show the lawyer’s reaction to the scars on Manka’s back, and this shows that these cameras can move quickly, but also do not require professional camera operators to be used and capture good quality footage.

The near infinite storage space on these cameras allows for Longinotto to record for as long as is needed, and avoid interrupting events and proceedings to get a new camera. This is impactful as a documentary filmmaker, specifically an observational one, must avoid being a distraction for the participants of the film and interfering with the way that events play out. These lightweight and portable, accessible and compact digital cameras remain unobtrusive throughout the production process and prevent the film crew form being too involved in the events that they are documenting. The high quality of the camera footage also allows for the scars on Manka’s back and legs to be seen clearly by the audience, emphasising the severity of the aunt’s actions, and the zoom again helps here by allowing Longinotto to focus the audiences attention without moving herself. The long takes in this sequence also show to the audience that the footage here is unedited and untampered through editing, making the film feel more authentic and real.

Digital technology has had a significant impact on Sisters In Law. Lightweight, portable, compact cameras with near limitless storage space allow for long takes and for the filmmakers to stay unobtrusive in the films production, separate from events and avoiding interrupting proceedings. They also film in natural light conditions, and their non-directional, built in microphones allow for quality audio to be captured form all around an area without the need for a boom stick, which can be bulky, difficult to carry around and distracting for the film’s participants. Non-linear digital editing has allowed for Kim Longinotto to choose which clips she would want included in the final film, and what is not necessary, and make sure that events are kept in order and different audio and footage clips can be overlapped to make the film more entertaining and flow better, keeping only the most important clips in the final film.

Version 2:

Digital technology has impacted Sisters In Law (Kim Longinotto, 2005) to a large extent. Digital audio equipment, digital camera technology and non-linear digital editing have made it easier for Kim Longinotto to gain high quality footage and documentation of their subject without making any sacrifices during the production process.

In the opening sequence of Sisters In Law, the camera shows the view from inside a moving car, introducing us to the village the film will be set in. The digital camera stabilisation here captures the view from outside the window clearly, in good quality footage, and prevents the camera from shaking around and disrupting the quality of the footage. This is the first time that the portability of digital cameras can be seen in the film, as the camera being used here fits into the back of this small car. The first show we see of the office is a man parking his bike up. This shot, alongside those inside the office, were included in the final film after the editing process because Longinotto was able to film for long periods of time, capturing lots of footage of this village so that she could choose which clips to keep in the film. This is because the digital cameras hold near limitless storage, so that the filmmaker can film for as long as they want, as seen in the opening shot to this sequence, and decide what to include in the film in post-production. The lightweight nature and portability of digital cameras allows for Longinotto to film in these cramped office conditions without getting own the employees’ way, since the small camera can just be moved when needed. These digital cameras can also film in natural and low light conditions, as seen inside the office, without the need of obtrusive artificial lighting, and the end product of the footage is still high quality, as we can see the inside of the office clearly despite the lack of artificial lighting equipment.

There is also no need for a boomstick to pick up audio here, since there is a non-directional camera built into the camera. This means that there is no large audio device taking up space in the room, making sure that no employees are distracted by the camera crew since their small and portable equipment keeps them unobtrusive. This non-directional microphone also does not need to be aiming at a specific subject to capture audio from them, and just one digital camera can capture good quality audio from around the entire room without using bulky, heavy and obstructive equipment, as seen when a woman speaking in frame can be heard at the same time as a man who is sat outside of shot. Digital cameras are also cheaper than film cameras, so two were bought for Sisters In Law, and we can see this from how the film cuts between them both. This allows for more footage to be captured, as seen here from where the camera cuts from a shot of a woman setting up her desk in the office and answering a phone to a man in the lawyer’s office the next room over. But despite there being more cameras here, they still take up little more space as they are so small and portable. The audio from the office has also been edited to play over the footage of man in the lawyers office, so that we can hear the conversation playing out in one place but also be immersed in the environment from the clip of the office, making us, the audience, feel like we are really there. The digital camera can zoom in on objects of significance, such as the wife who is giving her story in the lawyers’ office, to focus the audience’s attention on them without physically moving the camera and distracting the participants. The compact nature of the cameras also leads to people sometimes forgetting that they are there and giving a genuine reaction to things, seen in Sisters In Law when the lawyer shouts “That’s what you men do” at the husband, which allows for more authentic aspects of these people and life in the village to be captured.

The near infinite storage space on these digital cameras, made possible by SLR memory cards, allows for Longinotto to record for as long as is needed and avoid interrupting events and proceedings to get a new camera or new film tape. This is impactful as a documentary filmmaker, specifically an observational one, must avoid being a distraction for the participants of the film and interfering with the way that events play out, seen in Sisters In Law when the lawyer has an outburst of anger against the aunt who beat Manka. These lightweight and portable, accessible and compact digital cameras remain unobtrusive throughout the production process and prevent the film crew from being too involved in the events that they are documenting by walking around or taking up space, reminding participants of their presence there. The high quality of the camera footage also allows for the scars on Manka’s back and legs to be seen clearly by the audience, emphasising the severity of the aunt’s actions, and the zoom again helps here by allowing Longinotto to focus the audiences attention without moving herself. The long takes in this sequence also show to the audience that the footage here is unedited and untampered through editing, making the film feel more authentic and real.

Digital camera technology has also had a significant impact on the production of the Manka sequence. The camera is small and compact, remaining unobtrusive in the lawyer’s small office as it takes up significantly less space than a film camera would. This prevents it from being distracting at any point for the participants in the documentary, such as the small child Manka, who does not look at it more than once throughout the whole scene. It also allows for Longinotto to point the camera at whatever is relevant in a specific moment, such as the lawyer, who she pans right to show as she gives a reaction to the aunt’s actions. The lawyer’s reaction, a brief moment of anger, was also made possible by the size and portability of the digital cameras, as the lawyer likely forgot that they were there and so gave a completely honest reaction in the heat of the moment. These digital cameras can also zoom, so Longinotto can bring the audiences specific attention to something, such as the aunt’s reaction to what she has done when it zooms in on her face as the lawyer questions her, or in this case the scars on Manka’s back, making the audience feel sympathetic for her and avoiding having to physically move closer to capture it on camera, interrupting the proceedings. The camera also automatically refocuses when it pans right to show the lawyer’s reaction to the scars on Manka’s back, and this shows that these cameras can move quickly, but also do not require professional camera operators to be used and capture good quality footage.

So overall, digital cameras, non-linear digital editing and digital audio equipment has had a significant positive impact on the production of Sisters In Law. They allow for Kim Longinotto to operate with a small camera crew and lightweight, portable cameras that remain unobtrusive and capture quality footage in natural conditions, with the digital memory card storage capability allowing for long, uninterrupted takes that make it possible to capture unexpected events during production, such as honest reactions from the participants. The digital audio equipment allows for the film crew to remain stationary as they record and captures what is needed, remaining unobtrusive by reducing the need for boomsticks, and the non-linear digital editing means that Kim Longinotto can take what footage she finds most essential to the film and include it in post-production to keep events in chronological order for the audience.

You must be logged in to post a comment.