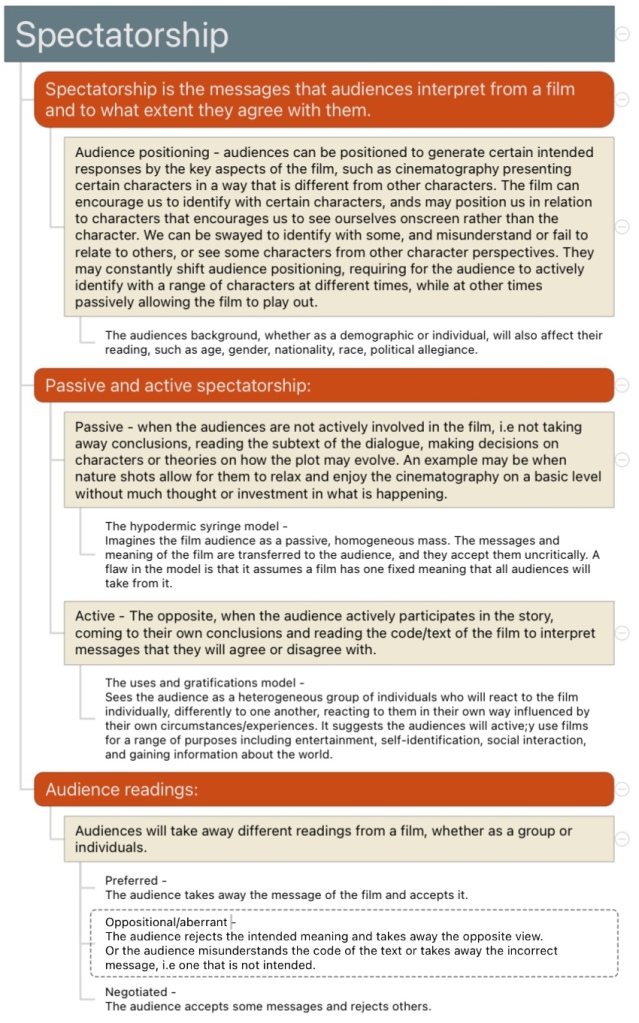

Explore how far the two films you have studied demonstrate the filmmakers’ attempt to control the spectator’s response.

Plan:

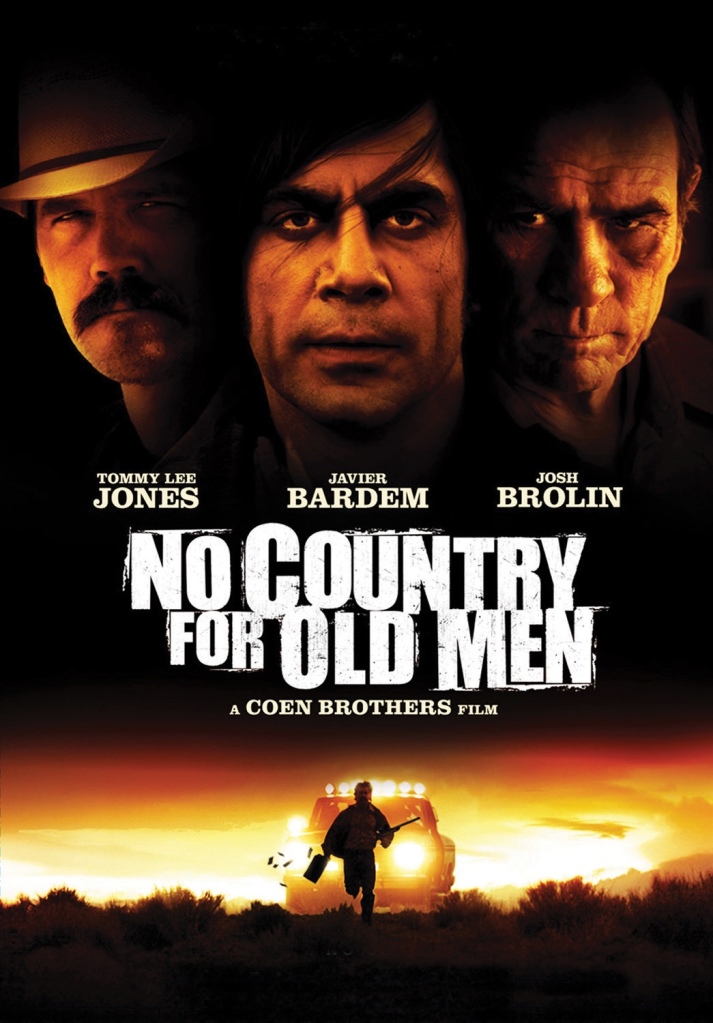

Intro – The filmmakers of Winter’s Bone demonstrated this to a large extent, as the spectators are encouraged to emphasise with the female characters, specifically Ree, who represents a group of repressed women, and encourages the audience to oppose the men in the film, who are represented as oppressive and ignorant. No Country For Old Men does not demonstrate this to as much an extent, as the film’s deliberate denial of conventional audience viewing pleasures, like a satisfying ending or a climax to a tense scene, leaves the film’s messages and themes more open to interpretation.

Winter’s Bone squirrel dream sequence, how it encourages us to emphasise with Ree.

Winter’s Bone squirrel gutting sequence, how Teardrop is represented as belittling and arrogant, in contrast with Ree, who is presented as an unconventional parental figure.

No Country For Old Men opening sequence, the film does demonstrate the attempts to provoke the audience to feel disgust at the killings, and like Moss through his careful and wise demeanour. However, his tracking the money and not giving the suffering man any water contradicts this, and presents him as a more ambiguous protagonist, one who we may not like.

Coin toss sequence, how Anton is made ambiguous by showing the man mercy against our expectations, and also how the scene denies conventions and allows the audience to come to their own conclusions/responses on the themes, meanings, characters of the film.

Ending sequence – no shootout, sudden character death, one character simply retiring, all leads to a denial of convention, forcing the audience to come to their own conclusions, also seen in cars crash scene and Anton’s reasons for killing Jean.

Conclusion – Winter’s Bone demonstrates the filmmaker’s attempts to control the spectator’s ]response, but No Country For Old Men largely doesn’t.

Essay:

Winter’s Bone demonstrates the filmmaker Debra Granik’s attempts at controlling the spectator’s response to a large extent due to the encouragement for them to empathise with the women of the film and oppose the men via representations of the two groups. However, the filmmakers of No Country For Old Men, the Coen Brothers, do not attempt to control the spectator’s response as to as high an extent, as the film denies many audience expectations and conventional viewing pleasures to encourage and allow them to come to their own conclusions.

Winter’s Bone demonstrates Debra Granik’s attempts at controlling the spectator’s response to a large extent, as seen in the squirrel dream sequence, where the spectator is encouraged to empathise with the protagonist Ree. The squirrel in the dream is shown to represent Ree through the juxtaposition of shots of it and smaller squirrels, reflecting Ree’s responsibility as a protector of her younger siblings. The increase in the editing pace of shots of the squirrel, in distress, alongside a sharp and jarring rise in the diegetic sound mix of a wood-saw, shows that the squirrel in terrified at the sign of impending danger, further shown through shots of trees burning, and the squirrel clinging onto its tree, its home. The spectator is encouraged, therefore, to sympathise with Ree, shown here to be clearly struggling to protect her home and family from the impending danger of repossession and homelessness in the winter. We also associate the blaring diegetic sound of wood-saws with the men of this traditional rural community, showing them to be the source of Ree’s struggle. Therefore, the filmmaker’s attempt to influence the spectator to empathise with Ree and oppose the men who are causing her problems, reflected in this dream sequence.

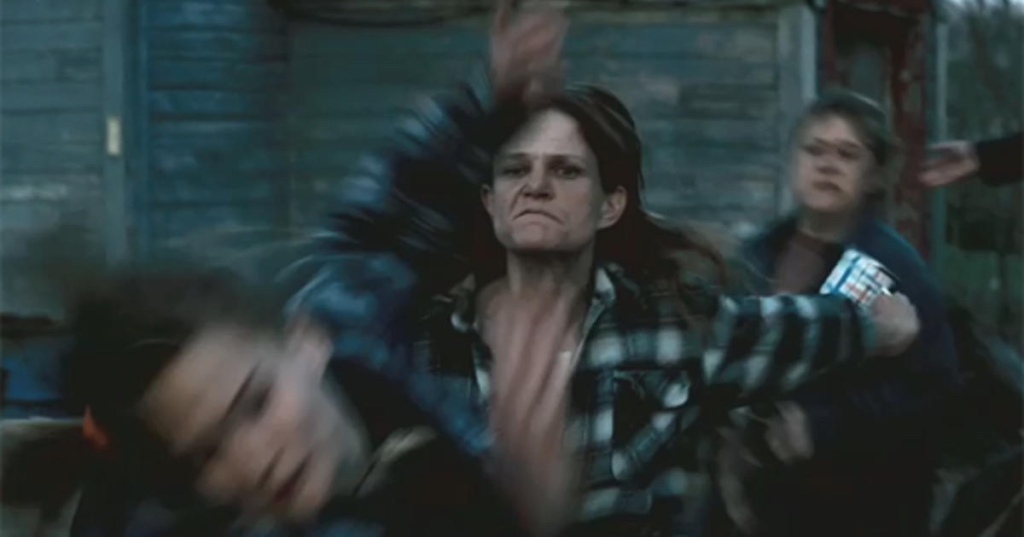

The filmmakers of Winter’s Bone also attempt to control the spectator’s response to admire Ree and her tenacity as a parental figure, and oppose the film’s antagonists, men, represented by Teardrop in the squirrel gutting sequence. Here, Ree is shown to be an unconventional role model to her siblings, teaching them to hunt despite being a woman, filling in a traditionally male role in this patriarchal community. The low angle shot of her aiming a rifle with the two younger siblings beneath her highlight her strength and defiance of the conventions of the male-dominated system. In this way, Granik attempts to influence the spectator to respect Ree, who goes against unlikely odds in this orthodox, sexist community for the sake of her family’s welfare. The audience is also influenced to oppose and dislike the men of the community, represented by Teardrop, whose clothing is dirty, with an unkept face that presents him as a repulsive human being. He belittles Ree by grabbing her face, showing that he feels he has power over her, as he is a man, and also mocks her by waving cocaine in her face, taking some himself and so highlighting the character’s degradation. Ree’s defiance, however, by meeting his eyes and refusing to be intimidated by his aggression, further encourages the spectator to support her and root against Teardrop.

Whereas Winter’s Bone demonstrates it’s filmmakers’ attempts to control the spectator’s response to a large extent, No Country For Old Men makes it’s themes more ambiguous and, therefore, open to interpretation, as seen in the opening sequence. At first, the spectator is encouraged to view Anton as a clear-cut villain and Moss as a stoic protagonist. The brutality of Anton’s initial murders of innocent people in contrast to his seeming lack of emotion represents him as an inhuman sociopath, and so the spectator is encouraged to disagree with this actions. Moss, on the other hand, is portrayed as calm, composed and intelligent, carefully surveying a crime scene and assessing where the money could have gone to with a careful methodology, presenting him as a responsible, experienced veteran. Therefore, the spectator is encouraged by the filmmakers to support him on his journey. However, the characters are not entirely clear-cut in how they are represented as good or bad. Moss, for example, does not aid the dying man begging for water, and kills a wild animal while hunting, which presents him as cold and relatively uncaring of other’s suffering. He also decides to steal the money he finds, with no explanation of why he does so. The spectator, therefore, is allowed to read the character’s actions independently, and may decide that he is doing it so support his family, or out of simple greed. In this way, the protagonist is not entirely good or conventional, and is left more ambiguous through his actions. Therefore, the Coen Brothers do not always attempt to control the spectator’s response.

The filmmakers No Country For Old Men also allow the spectator to respond independently of their influence or direction through the actions of Anton in the coin toss sequence. Here, Anton is established further as a cruel and intimidating figure, who seems to enjoy threatening an innocent gas station clerk and seeing the man’s frightened reactions and desperateness to get away from Anton, as evidenced by the line “You don’t know what your’e talking about” when the man says that he needs to close his shop. This prompts the audience to further dislike Anton’s character, however, the scene ends, surprisingly, without any bloodshed, Anton allowing the man to live because of his lucky call of a coin toss. This presents Anton as a man who only kills out of necessity, as seen in his murder of the police officer in the opening sequence to escape the police station. This small level of benevolence further perpetuates Anton’s image as an embodiment of death, leaving the spectator to come to their own conclusions on the character. Even if their reading of the film is aberrant, the Coen Brothers allow them to make respond to the messages and themes of No Country Of Old Men, without being fed information through explicit character actions.

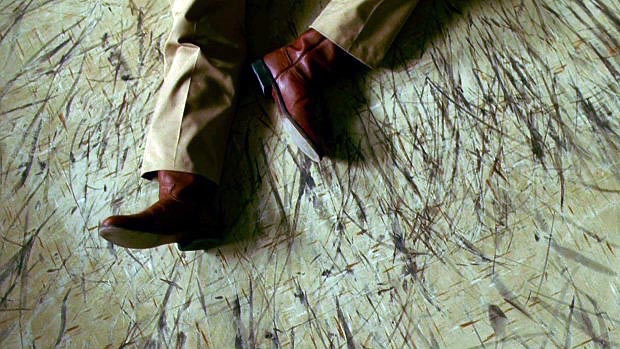

The Coen Brothers also do not attempt to control the spectator’s response in the ending sequence of No Country Of Old Men. In this sequence, the film ends in an anti-climatic way, Moss being killed offscreen before his final duel with Anton, and Sheriff Bell simply retiring. This abrupt and emotionally unsatisfying ending goes against typical western movie conventions where the distinctly and recognisable good protagonist triumphs against the detestable and undoubtedly bad antagonist, instead allowing the villain to live while the hero dies randomly and without dignity, shown to be lying in his own blood in a random motel doorway, killed by a group of unknown gangsters. The abrupt conclusion to this rivalry does not try to coerce the spectator into feeling happy or frustrated with the ending, as the ambiguous nature of the ending instead encourages them to come to their own conclusions. Although most audience members will likely feel unsatisfied at the sudden ending, they are given the freedom by the filmmakers to make their own minds up on what the meaning of the film is, and to respond in an individual way, rather than a conventional ending to the story telling them how to feel, i.e happy that the villain failed. The ending sequence also allows the spectator to respond independently by again presenting Anton as a somewhat merciful figure. Although he hunts done Carla Jean because of his promise to Moss to kill her, he gives her the option of staking her life on the coin toss. Her refusal to play, in his philosophy, essentially forfeits her life, and so the murder is to him, justified. Even though the spectator is encouraged to sympathise with Jean through her loss of husband and mother and clearly mourning for the deaths, having done nothing herself to provoke Anton’s aggression. Still, the spectator, while likely viewing Anton as cruel and uncaring, will see that he has a code he sticks to, and Jean refused her chance at survival, and so are given some measure of independence here in responding to the film Therefore, No Country For Old Men demonstrates it’s filmmakers’ attempts at controlling the spectator’s response to a small extent.

Winter’s Bone demonstrates it’s filmmakers’ attempts at controlling the spectator’s response to a large extent, as Debra Granik influences the audience to emphasise with and support Ree, a strong woman who stands against the injustices and inequalities of a male-dominated, sexist society, and encourages the spectator to oppose said society and the oppressive men in it, represented by the repulsive and mocking Teardrop. No Country For Old Men, however, demonstrates it’s filmmakers’ attempts at controlling the spectator’s response to a small extent as, although they are encouraged to view Anton as cruel and Moss as stoic and wise, both characters are given a sense of ambiguity, through Anton’s harsh but strict moral code and Moss’s cold lack of compassion and the ambiguous reasons for stealing the money, alongside the unconventional ending that does not force or encourage the spectator to respond positively to a typical victory of good over evil. Instead, neither side wins, and the spectator is allowed to decide the meaning and significance of the abrupt conclusion.

You must be logged in to post a comment.