Narrative:

Trainspotting –

The film begins with an ‘In media res’, or a cold open, beginning with a jarring shot of feet running from an unseen threat, belonging to an unseen person, with the non-diegetic compiled score playing ‘Lust For Life’ by Iggy Pop. The song is fast paced and upbeat, lending an immediate momentum and energy to the film. It also reflects a shared culture between the characters, who would have listened to this music from 1977 as they were growing up. It creates a sense of camaraderie between them, as they like the same music.

The film does not have a linear narrative, as the event we are currently seeing takes place about halfway through the story, just before Renton and Spud are arrested for theft. The scene itself is non-linear, randomly cutting to a disjointed football game and using freeze frames to introduce each individual character.

The editing style of the film keeps it in constant momentum, a rapid pace of progression immediately established through the cold open, accompanied by the jarring narration, an action sequence and lively music. They narration is used in the film to branch between scenes, so there is either something on screen keeping the audience engaged, or Renton’s all-knowing narration to keep them immersed in the story. This is why the film feels so quick. An example of this constant motion through editing is the motion match between Renton falling on the football pitch and him falling in the drug den.

The pace of the film is also kept fast by the almost constant camera movement, which keeps momentum between hard cuts from one scene to another. The camera movement is also accentuated through the fluid character movements, as they run on the football pitch or run from security guards through the streets, or just fall backwards onto a floor. The choice of songs also compliments the film, as ‘Lust for Life’ plays over the monologue accepting drugs and rejecting middle-class social values, and later in the film, ‘Mile End’ plays during the grim flat-share between Renton and Begbie in an increasingly trashed London flat. They also contribute to the pace of the film, the tone and pace of the songs matching that of the scenes, e.g., ‘Lust for Life’ is fast and lively. The pace is also contributed to through the almost poetic screenplay. This can be seen in the visual accompaniment of the narration, for example when Renton describes how much he hates when people say… then the film cuts out Begbie speaking directly to the camera in a dollying in low angle shot about how much he looks down on the use of heroin.

The films rapid momentum is also maintained through the blurring of time, done through huge time compressions and ellipsis. In this way, one sequence seamlessly leads into another. This can be seen in the transition to London as a location for the film, the city being introduced in a montage of shots of things that are clearly from London, e.g., famous street names, ice cream, tourists and pigeons. Parallel editing is also used to tell multiple stories at once, such as what happens to Spud, Renton and Tommie after the night at the club, which sets up later aspects of the film, like when Tommie becomes addicted to heroin due to his grief at losing his girlfriend.

The cinematography is also unique and interesting, as the film frequently uses jarring camera angles, e.g., the low angle shot from behind the men guarding the football net. This playfulness prevents the film from becoming too mired down in the grim situation the characters are in, and so the film is not a kitchen sink drama, more an expressive and often comedic depiction of careless drug use.

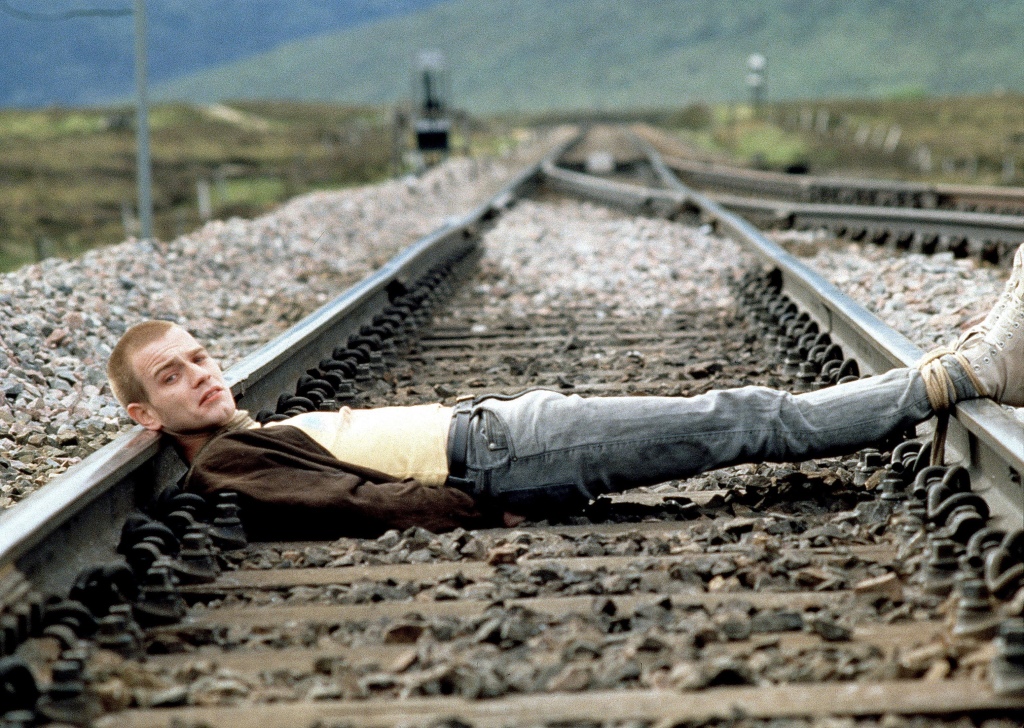

In the middle of the otherwise fast paced narrative, the film’s momentum slows down in an interlude, during which the main characters visit the great outdoors, where only diegetic sounds are used and the editing pace slows down. This brings our attention to Renton’s nihilistic outburst, keeping the audiences focus away from how the film was made and instead on Renton’s message, in which he mocks Scotland for being colonised by an even worse country.

Another instance in which the narrative sows along with the tone of the film is the sequence in which we learn of the neglected baby’s death. The editing slows done, the non-diegetic compiled score subdues, the film returns to more traditional camera work, and our attention is kept on the distress of the mother, and, like the characters, we are forced to confront the horrific situation that these people are in due to their addiction. This scene is one of the only in the film. That does not present a grim situation in a light-hearted and fun way, through playful cinematography, music, poetic narration or expressive dialogue or imagery.

This Is England:

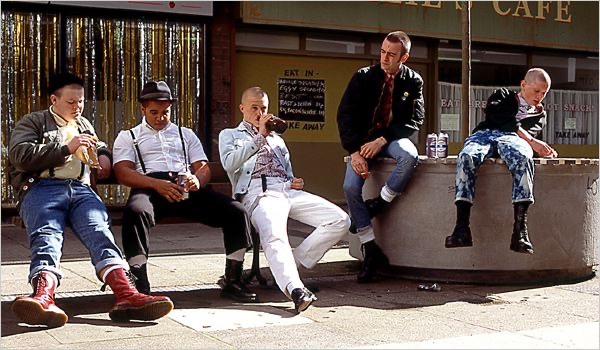

Whereas Trainspotting begins with a cold open to immediately immerse the audience in the world of the protagonists, This Is England begins with news reel stock footage from the 1980s, establishing the political climate of Britain in that time period. Culture is shown through footage of shows like Knight Rider and characters like Roland Rat, and the politics are established through footage of Margaret Thatcher, the Miner’s Strike, the Falklands War, Iranian Embassy Siege. This immerses us in the world that Shaun lives in. It conveys the mood of the time, a time of turmoil and change, and a lot of anger. Just showing Thatcher alone communicates this, as she was infamous amongst the working class for being highly pro-capitalist, conservative, with policies of privatisation and union limitation. Soul music is also played, as this was the origins of the skinhead movement; people dressed like that and shaved their heads to show their love for soul music, a traditionally black, cultural music form. Over time, this fashion movement was infiltrated and taken over by far-right nationalists, and this is what Milky and Combo dress the same way in the film. Different ideologies, same clothing. Milky even claims to be one of the first skinheads in the film.

Shots of the derelict area in which the film is set, working class homes in the town of Grimsby, establish the environment in which the protagonist lives. It also conveys an impact of Margaret Thatcher’s new house building schemes, which were intended to provide modern housing to replace the slums formed after WW2, but this housing soon became run-down and homogenous in appearance. A later shot of an abandoned, run down church with anti-Thatcher graffiti on it further conveys the attitudes of the area of society that Shaun lives in. Meadows uses this montage of visuals and music that define the era to root us in the setting of the story.

The films narrative is linear, the story and plot running largely in parallel. Meadows makes large use of ellipsis, however, to compress time, alongside montage to convey information. For example, when Shaun spends his summer holidays alone, and a montage with large time compressions is used to convey his loneliness. The same goes for when he is having a day out with the gang, where the film hard cuts to random shots of him and his friends hanging out and having fun. Upbeat, jovial music is okayed int eh non-diegetic composed score here to manipulate the audience into feeling happy for Shaun, alongside conveying his happiness at that time. The film is almost episodic in that there are large periods of linear storytelling before the use of a montage and large ellipsis. The disruption of equilibrium occurs in the bridge to the second half of the film, when Combo returns from prison.

Key Elements:

Trainspotting:

The film is highly expressive, using unique camera movements, lively pup music and unrealistic scenarios to convey addiction. In this way, the film gets to the truth of heroin addiction through comedy. For example, the scene where Sick Boy opens up his show sole to reveal a compact kit of heroin in there, which he then takes, despite wearing a suit. This moment, alongside the one in which Renton comedically breaks through a boarded up door to find heroin, are both cartoonish in nature, conveying the filth and squalor that they live in in a fun way. This can also be seen in the contrast between the highly red drug den and the oddly green hallway that the baby sits in as its mother takes heroin. Another example is when the scenes of the guys thieving places are played in montage, the music matched to the visuals, or when Tommy physically can’t lose the pool game with Begbie. Also, the use of classical music played over ‘the worst toilet in Scotland’ scene, an expressive moment itself, contrasting the filth of the moment with beautiful music, is played off for comedic effect.

This is England:

Shane Meadows takes subject matter that would traditionally be considered British social realism, but makes the films in a way that prevents them from being exactly kitchen sink dramas. This is because of his use of non-diegetic compiled music to in fluency the audiences reaction to the film. For example, when Combo returns from prison and immediately begins to spread his racist views, the diegetic score slowly subdues in the mix and the somber, emotionally manipulative non-diegetic compiled piano music rises in the sound mix. This is done to influence the audiences emotions here, influencing them to sympathise with Milky and oppose Combo. The exact same thing is done as Combo assaults Milky towards the end of the film, where we are manipulated to feel repulsed, horrified at what is happening.

Ideology:

The opening monologue by the omniscient Renton, separate from the one we see on screen, is a deliberate mockery of the ‘Choose Life’ anti-drug slogan. He sarcastically lists off typical, stereotypical characters of middle-class life like “electrical tin openers” and “compact disc players”. The monologue rejects these, and Renton claims that he chose something else, and why? There are no reasons when you’ve got heroin, he says. They reject an ideal life, career, family, etc. and instead choose heroin because they simply find it fun, pleasurable. This is a hedonistic ideology, as the characters embrace the pursuit of self-indulgence and arbitrary pleasure above all else. This can also be seen through Renton’s manic laugher at samosa being killed by a car, and the characters’ enjoyment of the hectic football game, or Renton’s seeming euphoria from smoking. It can also be argued that the film has a nihilistic ideology, as the characters reject all moral principles and accept life as meaningless, which Renton seems to be implying in this opening monologue. At the end of the film, Renton goes directly against this opening monologue, accepting this lifestyle, “choosing life”. In a sense, capitalism and Thatcherianism triumph. In this way, the film seems to claim that, ultimately, hedonism must give way to pragmatism, and nihilism leads to nothing.

Renton, despite his clear flaws, is immediately established as a likeable character. He is charismatic, and there is a poetry, even an intelligence too his opening monologue. This can also be seen in his monologue about Scotland, which itself is nihilistic, as he comments on the grim nature of his country, which he describes as a useless backwater nation of “wankers” colonised by “wankers”, and “all the fresh air in the world won’t make a fucking difference”.

This is England:

In the scene where Combo and his gang visit the political meeting in the rural pub, we get an insight into the operation of this organisation. In the 1980s, these political organisations that opposed immigration would campaign, but also used fear mongering tactics and violence against minorities, here represented by Combo. Combo himself speaks some logic to Shaun, which convinces him to join his gang. He speaks on the injustices and pointlessness of the Falklands War, which affected many people at the time, including Shaun, but targets his hate on the wrong group; minorities. His long monologue is done to remind audiences who were alive at that time period of some of the things they would have been hearing at the time, so Meadows is setting him up as a violent, hateful man, but one with a logic, despite how flawed it is. It shows how fine the line is between his political views and his prejudice, how one can lead to another, and what sort of thinking and ideology was attractive to these far-right nationalists. The justification for his hate towards the war is later shown through news reel footage from the time used in another manipulative montage towards the end of the film, in which we see what the war and the suffering it caused has achieved; a single, small village and scared, unarmed POWs.

This same footage is played right after Combo assaults Milky, cutting from him carrying Milky’s passed out body away, to a news reel shot of a British soldier erecting a Union Jack on a town hall roof in the Falklands. The film intentionally does this to contrast Combo’s actions with that of the British army. We see all that Combo’s ideology has achieved is violence and an almost dead friend, whereas the army has taken helpless POWs, lost lives, and all for the insignificant village shown. In this way, Meadows clearly communicated his opinion in a way that the audiences would have to work very hard to disagree with from watching the film. This is also conveyed in Shaun’s literal disposal of the St George’s Cross flag, a symbol of nationalism, into the ocean. The film argues that nationalism and racism cannot survive, and leads to nothing but violence. It also harkens back to the the behaviour of his gang earlier on in the film. Despite their intimidating appearance as a gang, as individuals they are pathetic, even laughable, who bully kids and harass women. They can put as much effort into a cause to belief, but in the end, what good does it do? The film is also conveying the dangers of patriotism in the juxtaposition between Combo’s ideology and imagery of the Falklands War. Combo’s obsession with pride in his country, and the country’s feeling of obligation to protect any meagre area of land it owns due to a sense of patriotism are shown to have harmful effects on innocent people, such as the fathers and wives waiting for the men to come home from the war, the POWs, the lined up bodies, and Milky, the women in the underpass, and the boys playing football. This is the result in pride over ones country, the film argues, and the rejection of these beliefs can be seen in Shaun throwing the England flag in the sea at the end of the film, both rejecting Combo’s ideals and vain patriotism.

You must be logged in to post a comment.